A catastrophic loss reveals the emperor penguin’s fragile existence in a rapidly changing Antarctica.

The silence is the most haunting part. Where the cacophony of thousands of fluffy, demanding emperor penguin chicks should be echoing across the sea ice, there is now a profound quiet. Coulman Island, the largest and most vital emperor penguin breeding ground in Antarctica’s Ross Sea, has become the site of an almost unimaginable tragedy. A stark press release from the dedicated scientists at the Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI) paints a devastating picture: the colony’s chick population has plummeted by an estimated 70% in a single year. In 2024, this nursery thrived with approximately 21,000 chicks. Today, only about 6,700 remain (Korea Polar Research Institute, 2025).

This wasn’t a predator attack or a mysterious disease. The culprit, as identified by KOPRI, was a silent, indifferent giant: a colossal iceberg. This immense slab of ice, a fragment of a collapsing ice shelf, drifted into a position that became a death sentence for thousands. It formed an impassable wall, severing the vital link between the colony and the open ocean, just as mothers were making their desperate journey back to feed their starving young. It is a brutal illustration of how the grand, slow-motion crisis of climate change can manifest as sudden, localized catastrophe.

Emperor penguin chicks on Coulman Island, presumed to have starved to death. Image courtesy of Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI).

The Making of a Tragedy: A Drifting Fortress

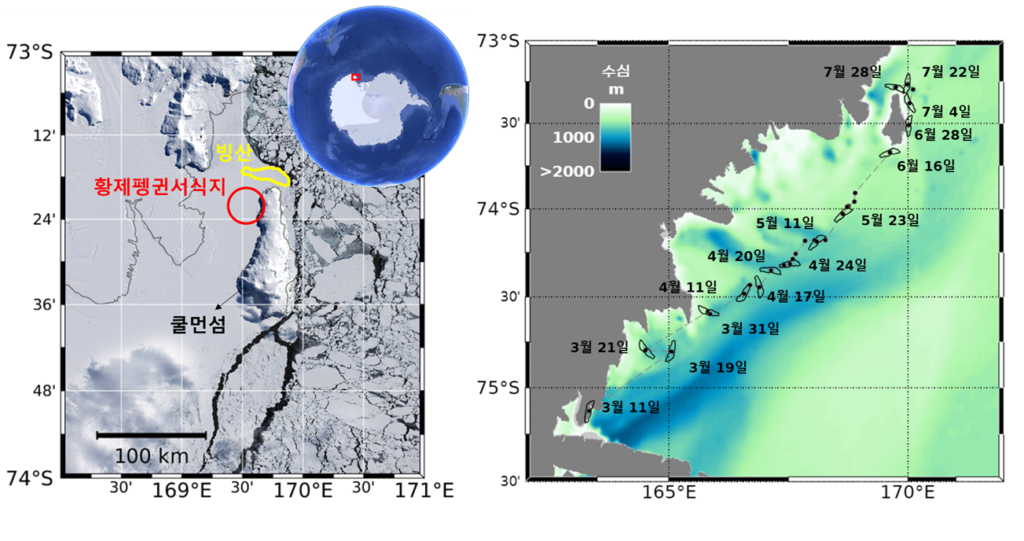

The story of this disaster, as pieced together by KOPRI researchers, begins months earlier and many kilometers away. In March 2025, a massive iceberg calved from the Nansen Ice Shelf. Such events, while natural, are increasing in frequency and scale as warming oceans eat away at the floating ice shelves that fringe Antarctica (NASA Earth Observatory, 2016; Dow & Lee, 2024). This particular iceberg was a behemoth measuring approximately 14 kilometers (nearly 9 miles) in length—an area equivalent to about 5,000 soccer fields. KOPRI researchers Kim Jong-woo and Kim Yumin confirmed its presence during a field survey, a giant blocking the colony’s main gateway to the sea (Korea Polar Research Institute, 2025).

For months, it drifted north on the ocean currents. Its path was random, its destination unknown. But satellite data analysis showed that in late July, it lodged itself directly in front of the Coulman Island colony. The timing could not have been worse. This was the precise moment the intricate, life-giving rhythm of the emperor penguin breeding cycle reached its most critical phase.

Emperor penguins have one of the most arduous parenting strategies on Earth. The breeding cycle begins in the Antarctic autumn (around April) when they gather on stable, land-fast sea ice (Australian Antarctic Division, 2008). In June, the female lays a single egg and, utterly depleted, transfers it to the male before embarking on a long, perilous journey to the sea to feed. For the next two to three months, through the darkest, coldest part of the Antarctic winter, the male stands alone, incubating the egg on his feet, fasting and losing up to 45% of his body weight in temperatures that can plummet to -60°C (-76°F) (SeaWorld, 2024; Gilbert et al., 2007). His survival, and that of the future chick, depends on huddling with thousands of other males to conserve energy.

Just as the chicks begin to hatch, the females are due to return, their bellies full of fish, squid, and krill. This first meal is life. But this year, when the mothers returned to Coulman Island, they found their path blocked. The iceberg, which hadn’t been there when they left, had created a sheer, unclimbable cliff of ice. KOPRI’s drone footage captured the heartbreaking evidence: “dozens to hundreds of adult emperor penguins” stranded at the base of the ice cliff, with “guano stains indicating prolonged stays” as they desperately tried to find a way back to their hungry chicks (Korea Polar Research Institute, 2025). For the chicks waiting on the other side, their mothers’ calls would never come. Dr. Kim Jeong-hoon, who led the research, explained the grim reality: “The surviving 30% were likely fed by mothers who found an alternative, unblocked route to deliver food.” He warned, “If the iceberg remains stationary for a long period, it could have long-term impacts, such as the emperor penguins moving to a different breeding ground.”

Adult emperor penguins (black dots) and guano stains (gray area) show where parents were trapped by the iceberg cliff, unable to return to their colony. Image courtesy of Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI).

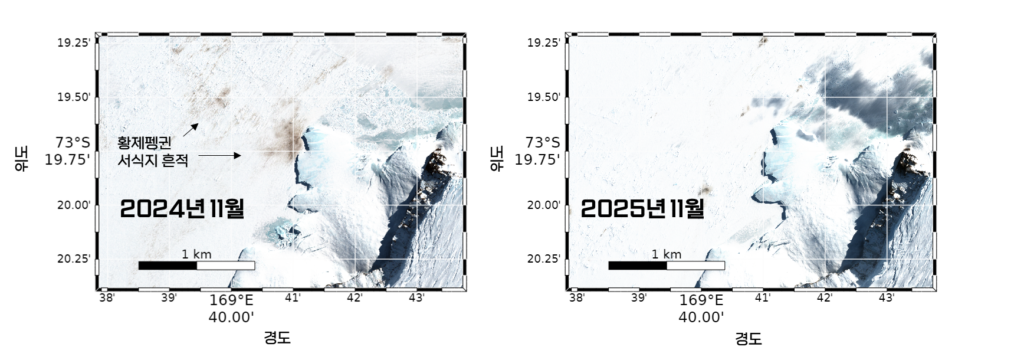

Comparison of the emperor penguin habitat on Coulman Island in November 2024–25.

In 2025, compared to 2024, traces of guano (brown areas in the left image) are barely visible.

An Echo of Disaster: The Bellingshausen Sea Failure

The Coulman Island tragedy, while shocking in its mechanism, is not an isolated event. It is part of a deeply worrying pattern. Just a few years ago, during the 2022-2023 breeding season, scientists from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) documented a different but equally devastating kind of breeding failure in the Bellingshausen Sea, on the other side of the continent.

There, the problem wasn’t a physical barrier, but the very ground beneath the penguins’ feet. In late 2022, the region experienced a 100% loss of sea ice in November, a period when emperor chicks are still covered in downy fluff and are not yet waterproof (Fretwell et al., 2023). Emperor penguins rely on stable, land-fast sea ice that persists from April all the way through to January for their entire breeding cycle. The chicks need this platform to survive until they fledge—the process of growing their waterproof adult feathers—which typically happens in December and January.

When the sea ice in the Bellingshausen Sea broke up and vanished weeks ahead of schedule, the consequences were absolute. Using Sentinel-2 satellite imagery, researchers observed that four out of the five colonies in the region likely experienced total breeding failure. Thousands of chicks, not yet ready for the frigid ocean, would have drowned or frozen to death. Dr. Peter Fretwell, the lead author of the study, stated, “We have never seen emperor penguins fail to breed, at this scale, in a single season” (British Antarctic Survey, 2023). This was the first time a widespread failure was directly linked to large-scale sea ice loss, a direct consequence of record-low Antarctic sea ice extent. Since 2016, Antarctica has seen the four years with the lowest sea ice extents in the 45-year satellite record, with 2022 and 2023 being the worst (NASA Earth Observatory, 2025).

Together, the Coulman Island and Bellingshausen Sea events highlight two deadly facets of the same climate-driven threat. Whether it’s the platform for life melting away too soon or the collapse of ice shelves creating deadly obstacles, the fundamental habitat that emperor penguins have relied upon for millennia is becoming dangerously unpredictable.

Sentinels on Thin Ice: What Other Penguins Tell Us

The plight of the emperors is a dramatic headline, but they are not the only penguins sending distress signals from the Southern Ocean. Their smaller, feistier cousins, the Adélie and chinstrap penguins, are also considered crucial “indicator species,” meaning their health and population trends reflect the overall health of the Antarctic ecosystem (ASOC, n.d.; Che-Castaldo et al., 2017).

Adélie penguins, one of only two species (along with emperors) that are true Antarctic residents, have a complex relationship with sea ice. While too much sea ice can force them to travel farther to find food, a lack of it is also perilous. Sea ice is a critical habitat for Antarctic krill, their primary food source, and is also used by the penguins for resting and molting (LTER Network, 2024; Schmidt et al., 2023). In the Antarctic Peninsula, where warming is most rapid, some Adélie populations have declined by over 65% in the past 25 years as their icy habitat shrinks and krill becomes scarcer (WWF-UK, n.d.). These plucky birds, famous for their “feisty attitude” and the males’ charming habit of offering pebbles to prospective mates, are facing a food web in turmoil.

Similarly, chinstrap penguins, easily identified by the thin black line under their beaks, are experiencing severe declines. A 2020 global assessment found that many colonies had shrunk, with some populations in the South Shetland Islands declining by over 50% since the 1980s (Strycker et al., 2020; Stony Brook Statesman, 2020). A 2025 survey of a major colony at False Round Point, King George Island, found a staggering 59% decline in 45 years (Hinke et al., 2025). Like the Adélies, this decline is strongly linked to a reduction in their main food source, Antarctic krill, which is struggling due to warming waters and the loss of sea ice (Trivelpiece et al., 2011). The fact that both ice-dependent (Adélie) and more ice-avoiding (chinstrap) species are declining in the same regions points to a fundamental disruption at the base of the food web, a disruption driven by climate change.

A Future on Melting Ground

For the emperor penguin, a species so uniquely adapted to the most extreme environment on Earth, climate change is considered the single greatest threat to its long-term survival. Their populations have not been impacted by hunting or direct habitat destruction in the modern era, making them a pure barometer for the effects of global warming (Fretwell et al., 2023). The scientific projections are chilling. If current warming trends persist, models predict that over 90% of emperor penguin colonies will be “quasi-extinct”—meaning their populations are doomed to irreversible decline—by the end of this century (British Antarctic Survey, 2023).

The KOPRI report underscores this unpredictable future. Dr. Park Jin-goo, who analyzed the satellite data, noted the broader danger: “The travel path of the iceberg that calved from the Nansen Ice Shelf also passes other major colonies… This shows that the collapse of ice shelves can pose a potential threat to emperor penguins and other species” (Korea Polar Research Institute, 2025). The work of organizations like KOPRI is therefore more critical than ever. They plan to officially report the Coulman Island findings to international bodies like the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), the body responsible for managing the Southern Ocean. This information is vital for the management of the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area (MPA), the world’s largest, and for informing decisions about fisheries and conservation across Antarctica.

Shin Hyeong-cheol, President of KOPRI, put the event in stark context: “This incident demonstrates how climate change can bring unpredictable risks to the Antarctic ecosystem.” He affirmed his institute’s commitment, stating, “We will strengthen satellite monitoring and field investigations through the next breeding season and continue to study the impact of climate change on the Antarctic ecosystem” (Korea Polar Research Institute, 2025). The tragedy on Coulman Island is a story written in ice and silence. It’s the story of a parent’s journey cut short, of a nursery that never had a chance. But it is also a warning, broadcast from the bottom of the world. The emperors, Adélies, and chinstraps are the sentinels, the canaries in the global coal mine. Their struggle for survival is a direct reflection of our planet’s health. The silence on Coulman Island is a sound we must all hear, a call to action that we can no longer afford to ignore. The fate of these magnificent birds is inextricably linked to our own, tied together by the same climate, the same ocean, and the same urgent need for change.

#EmperorPenguin #PenguinFriends #Antarctica #ClimateChange #Conservation #SeaIce #CoulmanIsland #KOPRI #ProtectTheAntarctic #PenguinConservation #ClimateCrisis #WildlifeConservation